Lessons to Understand Art History

The Open Seam: Torbellino 1—the Dance of the Hummingbird – Ndukun

19 March, 2025WhiteBox NYC.

Revaluing Feminine Trajectories and Stitching Alternative Genealogies in the Work of Yohanna Roa

By Karen Cordero Reiman

“As a verb […], ‘to craft’ seemingly means to participate in some small-scale process. This implies several things. First, it affirms the results of involved work. This is not some kind of detached activity… To craft is to care…. [It] implies working on a personal scale—acting locally in reaction to anonymous, globalized, industrial production…. It may yet involve the skilled hand. Hands feel, they probe, they practice.”

–Janis Jefferson[1]

Yohanna M Roa Is a New York-based artist who lives and works in a transnational and interdisciplinary mode; she grew up in Colombia and studied art there, then pursued graduate studies in art, anthropology and screenwriting in Mexico and simultaneously completed a doctorate in Art History in Mexico and an M.A. in Women’s and Gender Studies in New York, while also continuing an active career as a visual artist with exhibitions and ongoing projects in Colombia, Mexico and the U.S. These seemingly diverse spheres of activity are intertwined in her creative process, which draws on a firm sense of a maternal genealogy, as well as a fascination with the relationship between the materiality of art and archives, and the possibility of transforming social consciousness by making visible, intervening and articulating apparently opposed realms of material culture from the perspective of women’s experience and subjectivity.

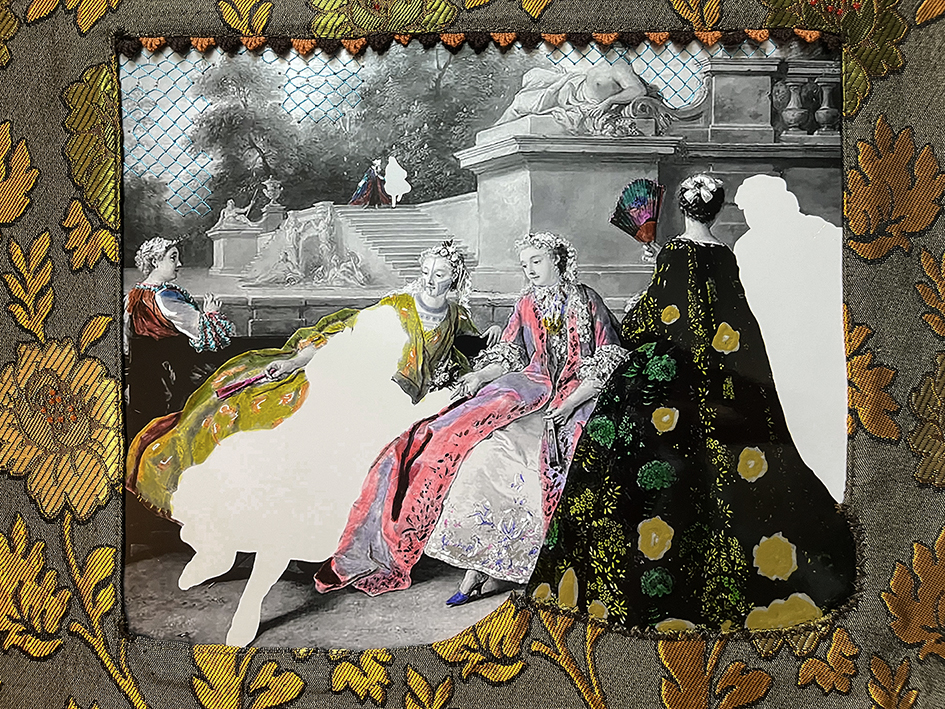

Roa’s work reincorporates into Art History the materiality that its disciplinary trajectory has wrenched from it, in its effort to rationalize the sensorial quality of art in verbal terms, to provide it with a structure and a canon, and to integrate it into The History of the Western World, with capital letters. In this exhibition, she literally dismembers books containing canonical images of art, and reconfigures them in new formal and conceptual relationships (among them, as domestic textile objects and clothing) through interventions using embroidery, crochet, collage and painting. Through this process they come to constitute a “virtual feminist museum” in the sense enunciated by Griselda Pollock[2]: a construction that subverts the rules of chronology, gender, style and geography that sustain hegemonic narratives and definitions of art, inviting new readings or modes of experiencing history through the corporeal acts of inhabiting, touching and manipulating the pieces.

The decisive accent that the works in this series place on physical experience and its specificity, makes the act of writing about them almost an act of sacrilege. They allude forcefully to the limits of verbal language and the categories that structure aesthetic experience, denouncing the poverty of a construction that denies female participation, as well as that of folk art and applied arts, non-Western aesthetic conceptions and other artistic creations that are distinct from or in resistance to art historical tradition and the geographic and political dominance of Europe.

With exquisite technical precision that reveals a masterful (or—rather–mistressful) handling not only of conventional academic techniques but also of sewing, weaving and restoration, Roa’s pieces cut across borders to construct a new artistic continent that we can inhabit and manipulate. She uses the pages from books to create dresses based on traditional designs of indigenous groups and other objects that reveal a hybridization between fabric, paper, thread and yarn, in a deliberate dismantling not only of the hierarchies that have separated the Fine and Manual Arts since the Renaissance, but also of our conventional habits of perception and presentation of art works, that tend to privilege a reflexive distancing from the object.

Through a subtle, eloquent and elegant procedure of montage and superimposition, Roa produces in her works a palimpsest of design elements from diverse cultural traditions that impedes our unmediated access to the European images from the Renaissance and Baroque periods in the books that are the material basis for her creations, making palpable the fact that our perception is always situated and incomplete. Our vision of the world emerges as a sensory act tied to the specificity of our bodies as cultural and gendered constructs, and Roa’s work articulates its fragmentary, imbricated, contradictory and incomplete quality, precisely the quality that the homogeneous and harmonious construction of conventional Western art history seeks to hide.

Yohanna Roa interrogates the history of art from a critical and anachronistic perspective[1], and at the same time, through her creations, exercises the act of mending and reconstructing a suggestive history of the images from a perspective of difference, alterity and multiplicity, not as another fixed proposal, but as a performative act in which the body—her body and our bodies–plays a leading role as a site for the construction of meanings and subjectivities.

[1] Janis Jefferson, apuntes para la exposición Boys Who Sew, citada en Shu Hung y Joseph Magliaro, eds. “Introduction” en By Hand: The Use of Craft in Contemporary Art (Nueva York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2007), 12.

[2] Griselda Pollock, Encounters in the Virtual Feminist Museum: Time, Space and the Archive (Londres y Nueva York: Routledge, 2007).

[3] Georges Didi-Huberman, “Apertura: la historia del arte como disciplina anacrónica” en Ante el tiempo: Historia del arte y anacronismo de las imágenes, 2ª edición aumentada, traducción y nota preliminar de Antonio Oviedo (Buenos Aires, Adriana Hidalgo editora, 2008), 29-78.